Menu

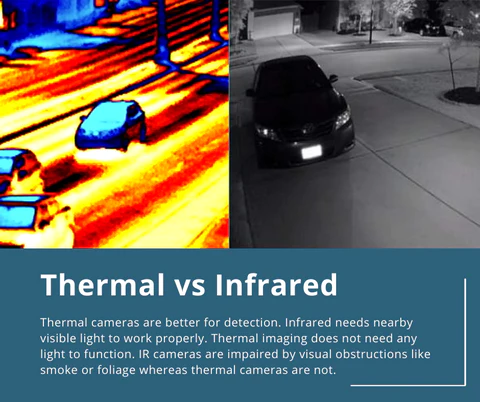

Active IR systems use short wavelength infrared light to illuminate an area of interest. Some of the infrared energy is reflected back to a camera and interpreted to generate an image. Thermal imaging systems use mid- or long-wavelength IR energy. Thermal imagers are passive and sense differences in heat. These heat signatures, usually black (cold) and white (hot), are then displayed on a monitor. Because thermal imagers operate in longer infrared wavelength regions than active IR, they do not see reflected light and are therefore not affected by oncoming headlights, smoke, haze, dust, etc.

Let’s start with a little background. Our eyes see reflected light. Daylight cameras, night vision devices, and the human eye all work on the same basic principle: visible light energy hits something and bounces off it, a detector then receives it and turns it into an image.

Whether an eyeball or in a camera, these detectors must receive enough light or they can’t make an image. Obviously, there isn’t any sunlight to bounce off anything at night, so they’re limited to the light provided by starlight, moonlight and artificial lights. If there isn’t enough, they won’t do much to help you see.

Thermal imagers are altogether different. In fact, we call them “cameras” but they are really sensors. To understand how they work, the first thing you have to do is forget everything you thought you knew about how cameras create pictures.

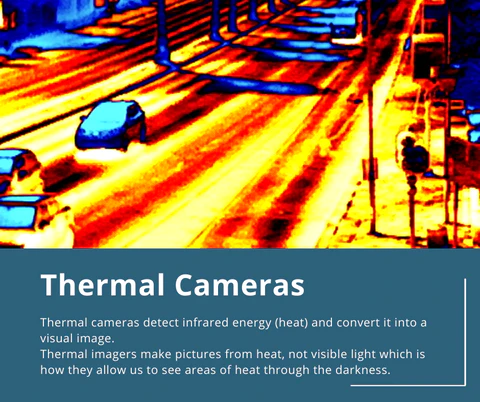

FLIRs make pictures from heat, not visible light. Heat (also called infrared, or thermal, energy) and light are both parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, but a camera that can detect visible light won’t see thermal energy and vice versa.

Thermal cameras detect more than just heat though; they detect tiny differences in heat – as small as 0.01°C – and display them as shades of grey or with different colours. This can be a tricky idea to get across, and many people just don’t understand the concept, so we’ll spend a little time explaining it.

Everything we encounter in our day-to-day lives gives off thermal energy, even ice. The hotter something is the more thermal energy it emits. This emitted thermal energy is called a “heat signature.” When two objects next to one another have even subtly different heat signatures, they show up quite clearly to a FLIR regardless of lighting conditions.

Thermal energy comes from a combination of sources, depending on what you are viewing at the time. Some things – warm-blooded animals (including people!), engines, and machinery, for example – create their own heat, either biologically or mechanically. Other things – land, rocks, buoys, vegetation – absorb heat from the sun during the day and radiate it off during the night.

Because different materials absorb and radiate thermal energy at different rates, an area that we think of as being one temperature is actually a mosaic of subtly different temperatures. This is why a log that’s been in the water for days on end will appear to be a different temperature than the water and is therefore visible to a thermal imager. FLIRs detect these temperature differences and translate them into the image detail.

While all this can seem rather complex, the reality is that modern thermal cameras are extremely easy to use. Their imagery is clear and easy to understand, requiring no training or interpretation. If you can watch TV, you can use a FLIR thermal camera.

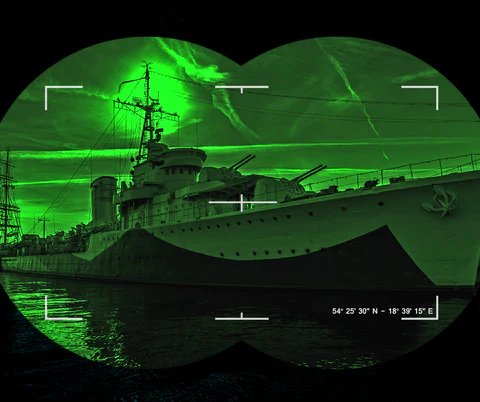

Those greenish pictures we see in the movies and on TV come from night vision goggles (NVGs) or other devices that use the same core technologies. NVGs take in small amounts of visible light, magnify it greatly, and project that on a display.

Night vision view

Cameras made from NVG technology have the same limitations as the naked eye: if there isn’t enough visible light available, they can’t see well. The imaging performance of anything that relies on reflected light is limited by the amount and strength of the light being reflected.

NVG and other lowlight cameras are not very useful during twilight hours, when there is too much light for them to work effectively, but not enough light for you to see with the naked eye. Thermal cameras aren’t affected by visible light, so they can give you clear pictures even when you are looking into the setting sun. In fact, you can aim a spotlight at a FLIR and still get a perfect picture.

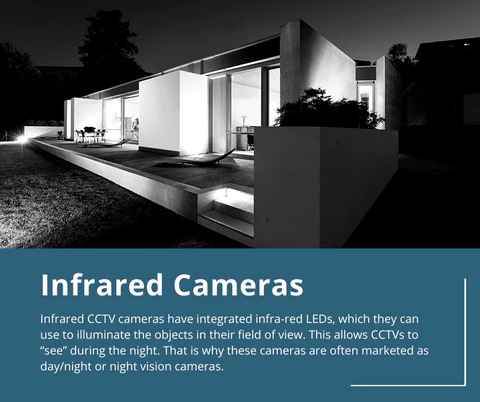

I2 cameras try to generate their own reflected light by projecting a beam of near-infrared energy that their imager can see when it bounces off an object. This works to a point, but I2 cameras still rely on reflected light to make an image, so they have the same limitations as any other night vision camera that depends on reflected light energy – short-range, and poor contrast.

All of these visible-light cameras – daylight cameras, NVG cameras, and I2 cameras – work by detecting reflected light energy. But the amount of reflected light they receive is not the only factor that determines whether or not you’ll be able to see with these cameras: image contrast matters, too.

If you’re looking at something with lots of contrast compared to its surroundings, you’ll have a better chance of seeing it with a visible light camera. If it doesn’t have good contrast, you won’t see it well, no matter how bright the sun is shining. A white object seen against a dark background has lots of contrast. A darker object, however, will be hard for these cameras to see against a dark background. This is called having poor contrast. At night, when the lack of visible light naturally decreases image contrast, visible light camera performance suffers even more.

Thermal imagers don’t have any of these shortcomings. First, they have nothing to do with reflected light energy: they see heat. Everything you see in normal daily life has a heat signature. This is why you have a much better chance of seeing something at night with a thermal imager than you do with visible light cameras, even a night vision camera.

In fact, many of the objects you could be looking for, like people, generate their own contrast because they generate their own heat. Thermal imagers can see them well because they don’t just make pictures from heat; they make pictures from the minute differences in heat between objects.

Night vision devices have the same drawbacks that daylight and lowlight TV cameras do: they need enough light, and enough contrast to create usable images. Thermal imagers, on the other hand, see clearly day and night, while creating their own contrast. Without a doubt, thermal cameras are the best 24-hour imaging option.